A large amount of research on Political Science is dedicated to answer the problem of political participation, with authors like Robert Putnam, in “Bowling Alone” (1995), observing that in the last decades there was a decline in the level and intensity of political activity. At national level, the concept of political participation is commonly measured by the Vote Turnout on the elections, as this is the largest institutional channel of Political Participation; is perceived as the simplest act of citizenship (Putnam, 1995) and has the most accurate and longest time series amount of data.

But this measurement is not perfectly assessed, as many individuals might be politically active in other channels – as participation in an activist group, writing to a congressman, protesting, etc. Sometimes, political active individuals choose not to vote even in a way of protest. It is difficult to measure exactly how many citizens are politically active, but the number could be estimated on a survey that question if the individual was recently engaged in any of the possible channels of political participation.

One propose here a different way to assess the size of politics, by text-analysis using Boolean Operators on Twitter data, during the presidential election campaign on 12 Latin American countries between 2013 and 2014 – Ecuador, Venezuela, Paraguay, Chile, Honduras, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Panamá, Colombia, Bolivia, Brasil and Uruguay. The sample includes the four months before the first or single round and one month after the second or single round.

Methods

Only a small fraction of Twitter data is geographically located – basically the activity that is on mobile devices. To estimate how many Posts can be found in a country (representing all the social activity available in one nation), first was performed a query using as keywords the Profiles on Twitter of the news services (TVs, newspapers and magazines) affiliated to the Inter-American Press Society (IAPS).

After accessing the Posts related to news, we sampled 1.000 posts for each country, to perform a text-analysis on the words available on Tweets from each country. Finally, we used the words that had an intrinsically political meaning (names of politicians, or political institutions, actions, framing, slogans) to perform another query, using both news names AND political words. This search will give all the posts from news services that were related to politics. It is worthy-noting that the result includes not only the tweets originally publicized by the news services, but also the re-tweets.

We understand that this is a better measurement of political activity on Twitter, as the data is related to the total of activity on Twitter, with news posts as a proxy representing the tweets within a single country. Commonly, we can only observe the number of Tweets within a single topic. And even if we find that this topic is Trending, one can only speculate what it represents comparatively to all the other Tweet activity in the same day.

Findings

The results are in the following table. As expected, we can observe that there is a wide variation on the “size of politics” on Twitter, from 3% of Posts in Uruguay to 74% in Venezuela. But most of the countries have a very low amount of political messages on Twitter, under 20% – which is impressive considering that the posts were counted during the electoral time.

Table: Size of politics on Twitter during Latin American Election

| Country | News posts | Politics posts | Percentage Politics |

| Ecuador | 646.086 | 63.119 | 10 |

| Venezuela | 5.944.929 | 4.414.143 | 74 |

| Paraguay | 469.844 | 39.551 | 8 |

| Chile | 899.027 | 65.797 | 7 |

| Honduras | 161.526 | 18.955 | 12 |

| Costa Rica | 153.542 | 24.156 | 16 |

| El Salvador | 337.541 | 50.260 | 15 |

| Panamá | 583.860 | 275.845 | 47 |

| Colombia | 5.327.258 | 837.028 | 16 |

| Bolívia | 63.557 | 12.760 | 20 |

| Brasil | 5.958.907 | 1.419.827 | 24 |

| Uruguay | 443.877 | 12.993 | 3 |

| Total | 20.989.954 | 7.234.434 | 34 |

Most interestingly, the outlier Venezuela has the most polarized electoral process, with only two main candidates obtaining nearly 50% of the votes each. To understand what are the reasons of this variation, one should conduct a more detailed analysis of the data. But we can assume that the explanation can be inferred not only by the analysis of the electoral and party system, but also by the media environment in each country and how it relates with the political institutions and actors.

It is also interesting to observe what are words found in most of the countries. impuestos (taxes), in 12 countries; presidente (president), in 11 countries; corrupción (corruption), in 10 countries; and gobierno (government), in 10 countries.

Next, we describe the parameters of the queries made on Twitter with Boolean Operators, and present a WordCloud of the most common terms, by country.

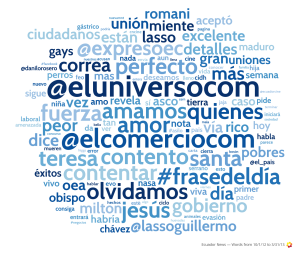

Ecuador

(@eluniversocom OR @elcomerciocom OR @Expresoec OR @revistavistazo OR @HOYcomec OR @lahoraecuador) AND (@chevron OR @lassoguillermo OR @mashirafael OR #debateec OR ciudadanos OR correa OR embajador OR exsecretario OR gays OR gobierno OR impuestos OR lasso OR nacional OR político OR rafael OR presidente)

Venezuela

(@globovision OR @ElUniversal OR @RCTVenlinea OR @diariopanorama OR @6toPodermovil OR @elimpulsocom OR @laverdadweb OR @Diario_ElTiempo OR @2001OnLine) AND (@chavezcandanga OR @hcapriles OR asamblea OR capriles OR chavez OR chávez OR ciudadano OR fascistas OR guerra OR maduro OR país OR presidente OR venezuela)

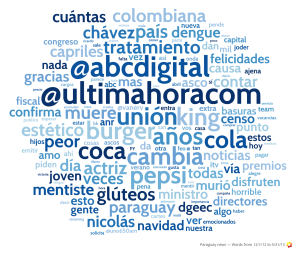

Paraguay

(@abcdigital OR @UltimaHoracom OR @vanguardiacde) AND (alegre OR cartes OR congreso OR destitución OR diputado OR electo OR fiscal OR gobierno OR impuestos OR irregularidades OR oposición OR políticos OR presidente)

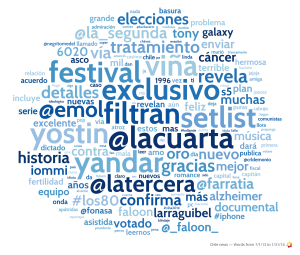

Chile

(@Emol OR @latercera OR @lacuarta OR @La_Segunda OR @DiarioLaHora OR @revistaqp OR @AmericaEconomia) AND (@fr_parisi OR bachelet OR comunistas OR derecha OR fiscal OR fronteras OR ideológico OR impuestos OR patria OR presidente OR votado OR votare)

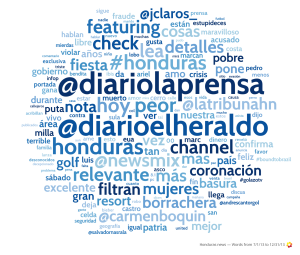

Honduras

(@DiarioLaPrensa OR @diarioelheraldo OR @LaTribunahn) AND (@salvadornasrala OR @salvadornasrala OR alcalde OR alcaldía OR corrupción OR corrupto OR corruptos OR gobierno OR impuestos OR impuestos OR nacional OR nacionalista OR pac OR partido OR patria OR presidente OR salvador)

Costa Rica

(@nacion or @DiarioExtraCR or @TheTicoTimes) or @cb24tv AND (@eldoctor2014 OR #crisisfiscalcr OR #eleccionescr OR araya OR autoridades OR candidatos OR constitución OR corrupción OR diálogo OR diputados OR elecciones OR evasión OR fiscal OR impuestos OR ministros OR nación OR pln OR política OR presidente OR pusc OR social OR solís)

El Salvador

(@prensagrafica OR @elsalvadorcom OR @ElMundoSV) AND (@arenanuncamas OR @arenaoficial OR @norman_quijano OR #eleccionessv OR alcalde OR arena OR campaña OR cargos OR compañero OR corrupto OR diputados OR exonerados OR fisco OR gobierno OR impuesto OR impuestos OR partido)

Panamá

(@tvnnoticias OR @prensacom OR @CriticaPa OR @PanamaAmerica OR @EstrellaOnline OR @DiaaDiaPa OR @elsiglodigitalV OR @MetroLibrePTY OR @capitalpanama) AND (@jc_varela OR @jdariasv OR @juancanavarro OR campaña OR democracia OR gob OR gobierno OR impuestos OR ley OR navarro OR noriega OR partido OR patria OR política OR politico OR prd OR presidente OR salario OR varela OR votos)

Colombia

(@ELTIEMPO OR @elespectador OR @elcolombiano OR @elheraldoco OR @elpaiscali OR @lapatriacom OR @ElUniversalCtg OR @larepublica_co OR @vanguardiacom) AND (lópez OR @alvarouribevel OR @juanmansantos OR @las_farcep OR @opina_colombia OR #eltiempomiente OR 1eravuelta OR cañones OR corruptos OR elecciones OR farc OR gobierno OR guerra OR guerrilla OR impuestos OR opositor OR presidente OR santos OR terroristas OR uribe OR zuluaga)

Bolívia

(@LaRazon_Bolivia OR @diarioeldeber OR @unitelbolivia OR @LosTiemposBol) AND (@boliviacomova OR @evompresidente OR @prisi41quiroga OR @yovotariaporevo OR #bolívar OR #eleccionesbo OR #mas OR cambios OR candidato OR candidatos OR elecciones OR gobernación OR gobierno OR impuestos OR morales OR partido OR paz OR policía OR presidente OR reinvindicación OR transportes)

Brasil

(@VEJA OR @JornalOGlobo OR @folha OR @Estadao OR @jornalnacional OR @RevistaEpoca OR @RevistaISTOE) AND (@dilmabr OR @dilmamentiu OR @leisparaquem OR @psdbmulherpr OR #abaixoódio OR #pt OR #youssef OR aécio OR campanha OR candidata OR corrupção OR corrupta OR corrupto OR corruptos OR debate OR democracia OR denúncia OR desemprego OR desmascarada OR dilma OR discurso OR eleições OR eleitores OR governo OR impostos OR incompetentes OR inflação OR levy OR luciana OR lula OR marina OR nazistas OR petistas OR planalto OR presidente OR protesto OR psdb OR pt OR racistas OR trabalhadoras OR youssef)

Uruguay

(@elpaisuy OR @ObservadorUY OR @canal10Uruguay OR @BUSQUEDAonline) AND (#debateateneo OR bordaberry OR colorados OR crisis OR drogadictos OR fiscales OR impuesto OR impuestos OR inflación OR oposición OR politólogo OR presidirá OR salarial)